What do riders learn by experience – trial and error?

What is not learned by experience, for which additional training is needed?

Summary

The background is a 8% increase in PTW KSI’s last year, and a recent 50% increase in young rider KSI’s. It’s currently aĺl going the wrong way.

There was a 14% increase in fatalities from 2023-24.

The DVSA data below indicates that it currently takes around 25 years, on average, for 80% of riders to master riding a motorcycle competently.

Far too long?

In order:- ‘Cornering‘, ‘Planning‘, ‘Defensive Riding‘, ‘Use of Speed‘ and ‘Overtaking – were found as the major rider shortcomings

‘Braking‘ and ‘Filtering‘ also stand out as particular extra training needs.

We now know what additional training is needed, and where current learner training and testing is falling short.

The Enhanced Rider Scheme looks to be effective, well managed and subject to continuous improvement.

In contrast, no benefits were found from current ‘Advanced’ training. (Agilisys).

Government action should be considered to make DVSA ERS licensed training far more available in the interests of public safety. This could easily be achieved by making DVSA trainer licensing compulsory for all commercial trainers. This would ensure, that the training is properly and safely conducted, and focused on the priorities.

The charities working in the sector, with volunteers, should also all be working to the same official standards.

History

The DVSA Enhanced Rider Scheme (ERS) was launched in 2006. It was to provide additional safety training for licence holders, particularly those returning to riding in later years.

Up to 1989 the examiner stood by the roadside, so it is only after this date that examiners followed riders on their test.

Compulsory Basic Training (CBT) was not introduced until 1990.

Currently most riders over 50 years old will not have had any training, nor been subject to a ‘pursuit’ licence test.

Findings

This is the data supplied by the DVSA following an information request. The speed of the response shows that the DVSA have clearly been closely monitoring the ERS Scheme, on an ongoing basis.

This is, I believe, the latest 5 years of data. The first observation is how relatively few riders are attracted to the scheme. This is the only post-test training in the UK delivered by qualified licensed trainers. That it is such a small number of riders, is a concern.

The vast majority of post-test training is performed by volunteers, or untrained unlicensed trainers, mainly to Police Roadcraft standards, but also sometimes encouraging ’emergency response’ and racing practises, such as trail braking by commercial trainers.

(A recent review by Agilisys found no benefits from traditional ‘Advanced’ training).

Agilysis report on Advanced Training

There is no other published rider assessments that I can find.

DVSA Data

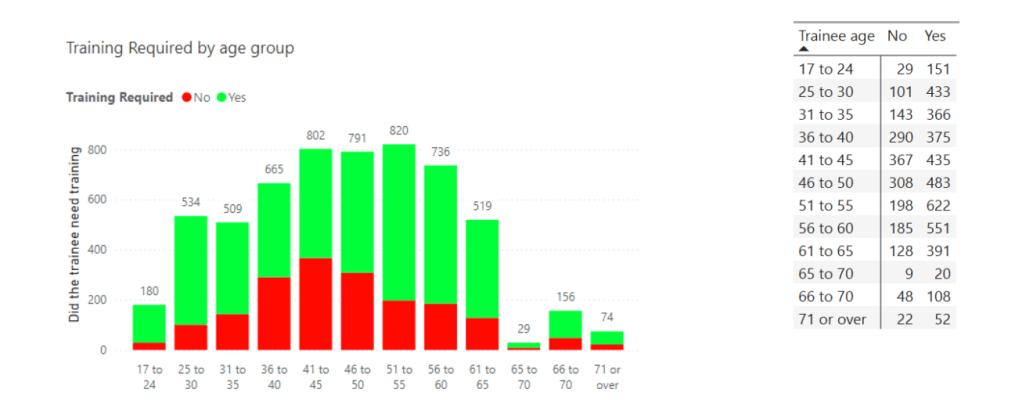

The bar graph shows the number of riders who needed, or who did not need, additional training following their riding assessments.

Green is needed training, Red is didn’t.

If you compare ERS attendees to the population of riders by age, you get this:-

Young riders look neglected? These are at the highest risk, so it looks like an opportunity?

The ERS scheme was aimed at ‘returning riders‘ and has hit the mark.

Training needs diminish up to 45, where the number of riders peak, then increases again. Strange?

There are are also two large peaks in training needs. 17-30 and 51-65 years – the Red bars vs the Green bars.

Training needed by age

If you present the data as the percentage of riders, by age, requiring training, a rather odd profile emerges.

Having stared at it for some time, and initially considering it as two separate distributions, a ‘light bulb’ moment.

You might have come across Dunning-Kruger before. It’s the journey from:-

‘Unconsciously incompetent’ to ‘Unconsciously competent’

The theory has been applied across many different fields. In this case the ‘Y’ axis is ‘training required’ – incompetence not confidence. However, it does look like younger riders don’t seem to be looking for more training, so could be over confident?

If you flip the graph, competence is shown to peak at 41-45 years. It then deteriorates as we move into later life.

It maybe a bit misleading, as the scheme is aimed at ‘born again‘ bikers, who have a big experience gap. And these will be riders who mainly felt they needed more training.

The riders over 50 will likely not have had training or a pursuit licence test, so are essentially a different group, who are mostly untrained.

Their apparent ‘lack of competence’ is reflected in the accident figures which are slightly higher. So there looks like there is a relationship between competence, as measured, and the risk of a collision.

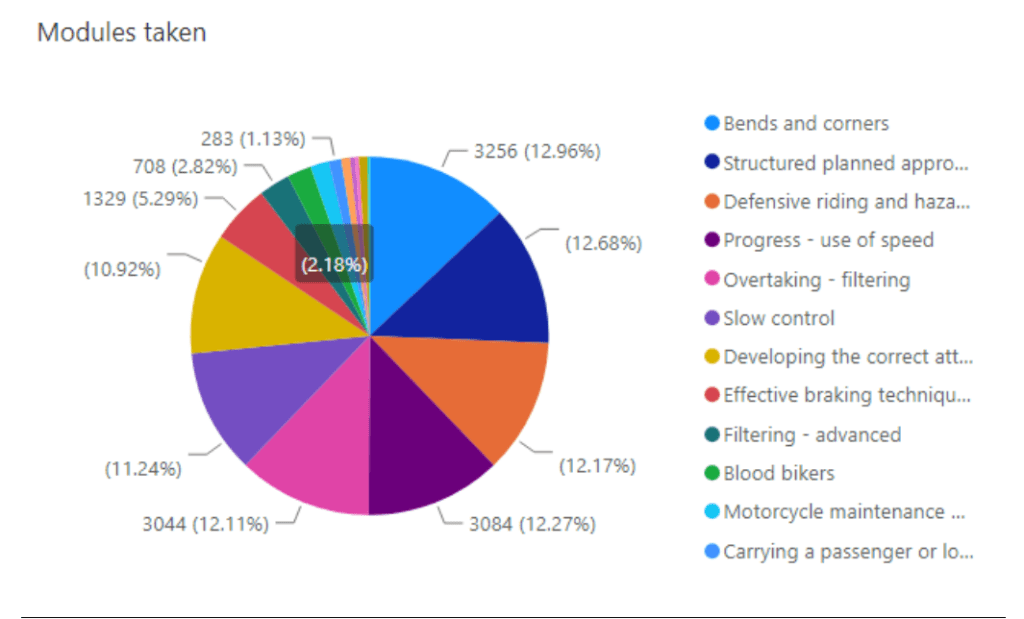

Modules taken

So what additional training was found to be needed to get riders up to standard?

You can see there is no particular training needs identified. They are various. Training needs are across a wide spectrum.

‘Cornering‘ tops the chart, followed by ‘Planning‘, ‘Defensive Riding‘, Progress and Overtaking.

Mastering Safe Cornering on the Road, with ‘Slow In Fast Out’ Technique

Extra Modules Taken

This is where rider needs are identified, that needed extra training.

This identifies ‘Braking‘ as the main need – more than a third of riders, and nearly twice the demand of the next module. Braking from higher speeds is not part of the licence test – just from 30 mph.

Probably circa 50% of riders cannot meet Highway Code braking distances from higher speeds, and many skid and fall in an emergency. It is encouraging that this is recognised and is being addressed.

Ultimate Guide to Emergency Motorcycle Braking

‘Filtering‘ is the second most popular training module, which is widely known to be hazardous.

Training vs Casualties (KSI).

If you add casualties by age (orange line), you now have a complete data set.

Young rider vulnerability is very clear. 10% of riders but 28% of the casualties.

After 30 years of age, KSIs roughly follows the rider population, with a divergence from 40-50, where the accident rate halves, before moving back to a standard KSI percentage.

So is the 40 – 50 group showing the results of experience? Or the peak of physical or mental ability? How much are older new riders part of the problem?

The answer is probably the lack of compulsory learner training and pursuit testing for the older riders, which only became compulsory in 1990.

If you look at the downward slope of the orange KSI line, there is an upward bump at 50 years which coincides with the introduction of CBT. It then continues downwards at the same slope but displaced upwards.

It will be interesting to see if this bump moves further along in the coming years.

Conclusions

It’s difficult to draw firm conclusions, but the data seems to confirm the positive impact of CBT from 1990. The ‘bump’ currently at 50 years should move along year by year?

But that currently leaves older riders at relatively high risk, which still needs addressing.

The high level of KSIs for younger riders is graphically illustrated, with a steep circa 10 year learning curve which also needs urgent action. This surely should be the priority?

The most obvious risk, which could be quickly addressed, is in young riders moving from a moped to a geared 125cc motorcycle with no additional training, despite the massively increased risk.

After 30 years old, the graph shows a steady decline in KSI’s which is probably continuous learning by experience, but at a lower steady rate.

This would seem an ideal opportunity to review learner training and testing (which will be ongoing internally within the DVSA) to address identified shortcomings in training.

Although inevitably, any major changes will have to be a political decision. This to balance the accessibility to PTWs, which are currently very high risk, with public safety.

The ERS scheme is currently poorly promoted and consequently very under-utilized, with far too few riders trained to likely have any effect. Only circa 1,000/year based on these figures.

The graph also suggests that ‘advanced’ training doesn’t currently fill the lack of learner training within older riders >50 years.

This would appear to support the recent Agilisys report, which found no benefits from advanced training.

Unqualified and unlicensed advanced trainers are currently allowed (probably illegally) to train riders commercially. This puts properly trained qualified and licensed DVSA trainers at a financial disadvantage, but more importantly potentially puts riders at risk,

The argument has always been that The Law states ‘driver‘ not ‘rider‘ trainers have to be DVSA licensed. However the CPS definition of ‘driver‘ is whoever is steering – by legal precedent I understand. This would include ‘riders’.

This could be implemented today.

The Enhanced Rider Scheme has been around for 19 years and is collecting data which will be used to improve training. The scheme has trained, tested, qualified, licensed trainers. They have a syllabus and standards to work to:- ‘Ride – The Essential Skills’. They are also regularly check tested whilst delivering the training.

It only costs around £1,000 for a week’s training to obtain a DVSA trainer’s license.

Government action is needed to make this compulsory, in the interests of public safety. Motorcycle riders are the most vulnerable road users by a margin, so need the best training available.

The ERS scheme is established and proven, so just needs fully implementing, as I believe was always intended.

We now know what is needed to get riders up to standard, and what the priorities are.

Police BikeSafe assesses circa 7,500 riders per year, with 20% or 1,500 going in to take further training. RoSPA and the IAM also provide ‘advanced’ training although the total numbers are not published, nor any findings.

Are they focussing on the same identified rider’s priority needs to stay safe, and shortcomings?

And as only 1,000 riders/year are being been ERS trained, with a population of 1.7 million, we’re all just scratching the surface.

Feedback and opinion encouraged.

Mike Abbott MBA, RoADAR (Dip), DVSA RPMT 800699, ACU Coach #62210

Advanced Rider Coaching

17.7.25

Updated 13.12.25